I once taught a second grader who sometimes subtly refused to go along with what we were doing. For instance, if we had to leave the classroom and John didn’t want to go, he’d get in line—but then walk as slowly as possible. The more his classmates and I urged him to walk faster, the slower he would go. At each deliberate step, I could feel my blood pressure rise. But in that moment, I could do little. I couldn’t physically make John walk faster; nor was he ready to rationally discuss his feelings or options. Rarely did a student’s behavior get to me, but John’s resistance always did.

When children are defiant, their goal is not to annoy, disrespect, or frustrate us. Rather, their goal often is to feel significant. Yet their defiance threatens our own similar need. As we both strive to feel significant, we can easily get enmeshed in a power struggle. How do you know you’re in a power struggle? You feel as if you’re being tested (which you are), and you get angry or irritated. You may even want to dominate the child to prove you’re the boss. But teachers never win power struggles. Once you’re in one, you’ve lost. And so has the child: No one wins a power struggle.

The best way to avoid power struggles and help a child who defies authority is to calmly work with him in ways that honor his genuine need to feel significant. Also critical is demonstrating that you still hold him (and everyone in the class) accountable for following the rules. And of course it’s best to help the child avoid defiance mode in the first place.

But how do you do all that while keeping your cool? Here’s a sampling of the practical techniques for addressing defiance presented in my book, Teasing, Tattling, Defiance, and More: Positive Approaches to 10 Common Classroom Behaviors.

The more you proactively give children constructive ways to experience personal power, the more cooperative they’ll be. Here are some proactive steps to try:

Although this advice applies to all students, it’s crucial for students who tend to act defiantly. These children need to feel that despite any difficulties, you’ll still care about them, recognize their successes, and actively include them in the classroom community.

To build strong relationships, remind yourself that all children, including those who frustrate you, have positive attributes. Make a point of learning about your students’ interests, and channel their talents in ways that foster their sense of significance. For example, a child who’s good with her hands could be called on to fix stuck door latches or other small mechanical problems in the classroom.

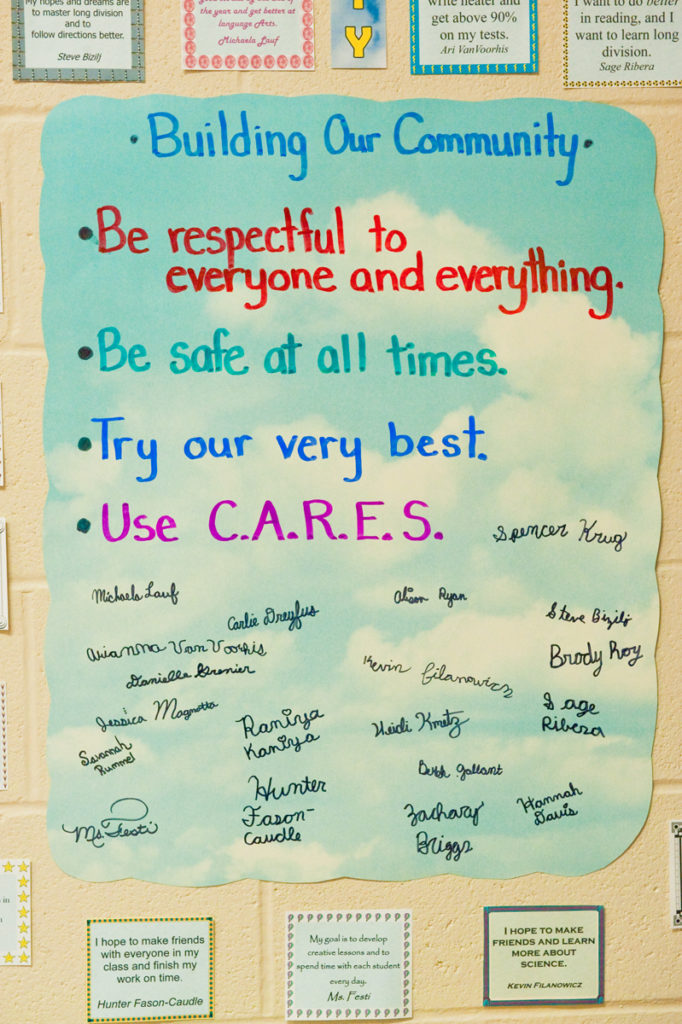

All children, but especially those who struggle with defiance, need to hear when they’re doing well and where they’re improving. Make a point of noticing the child’s successes (big and small) in following directions, transitioning smoothly, or doing anything that ordinarily might invite resistance. Reinforce the behavior by letting the child know you noticed, but do it privately to avoid calling attention to the child and inviting comparisons with classmates, and be specific. Whenever possible, also note how the cooperative behavior helps the child and others. For example: “When you get in line quickly, everyone has more time for recess” or “When you helped Kevin this morning, I think he felt valued. You were living out our rule to ‘take care of each other.'”

To avoid suggesting that pleasing you is what’s most important, steer clear of phrases such as “I like,” “I want,” and “I appreciate” when reinforcing positive behavior. A child who’s sensitive to being told what to do may feel manipulated by “I” statements.

It’s empowering for all children—especially those who struggle with authority—to know that they may disagree with adults. Of course, allowing students to disagree doesn’t mean accepting all forms of disagreement. Part of becoming a contributing member of a democratic society is learning how to disagree respectfully.

When teaching children appropriate ways to disagree, make clear that in the moment, they still need to follow directions and rules. Let them know that later they can discuss what they think was unfair and what should be changed.

Teach children safe and respectful ways to show their disagreement, such as using respectful words and phrases like “I feel that” and “I suggest,” or writing a letter to you or dropping a note into a complaint box. Be sure to model these methods before expecting children to use them.

Children who challenge authority are often quite adept at taking on bigger causes. Working on issues they consider important can help focus their energy and build their sense of significance. Offer assignments such as writing letters to the school or town paper, community service projects, or researching an environmental issue.

When a child is being defiant, you need above all to keep her (and her classmates) safe while giving her a chance to cool down. These general guidelines will help you and the child navigate episodes of defiance:

Following are some specific steps you can take to guide a child past active defiance.

When you first see signs that a child may become defiant, respond as soon as you can with respectful reminders or redirections. If you wait until a child has dug in his heels, he will likely be less able to respond rationally to your directions.

Students who have difficulty cooperating can be especially sensitive to being ordered around. Remember to:

For example, to a child who’s challenging directions by standing up and yelling, you might quietly say, “Andre, take a seat. You can read or draw for now.”

Once a child has become defiant, you may decide to use consequences. Remember, though, that children who struggle with defiance are often seeking power. Offering a choice between a couple of consequences (instead of giving a “do this” order) lets the child hold on to her sense of significance and dignity and teaches her (and the class) that she’s still being held accountable for her behavior. For example, when Anna refuses to move during a transition, you might say, “Anna, either you can come with us now, or I can have [name colleague] come sit with you. Which do you choose?”

Once a child has defied you, decide on a redirection or consequence and remain firm in your decision. Negotiating during the incident will invite further testing. It also sends the message that children can avoid a redirection or consequence by resisting.

If you do find yourself in a power struggle, take a deep breath and disengage. Let the child (and the whole class, if watching) know that you’re finished talking for now and will address the issue after the child calms down. For instance: “Max, we’re done talking about that for now. Everyone, get your writing journals out and start on your stories from yesterday.”

Once you’ve given a reminder, redirection, or consequence, be sure the child follows it. But physically step back to give him more space—literally and emotionally. Doing so lessens the sense that you’re trying to control him. But don’t expect immediate compliance. A child who struggles to follow directions often needs a minute or two to decide what to do. If you insist on immediacy, he may automatically resist.

It’s easy to feel angry, irritated, or frustrated when children defy us. But when we find ways to rise above our own feelings, we can continue to appreciate our students and guide them beyond defiance. The result: We grow as teachers, while offering the children a path to success and a model of how to get along in the world. Learn more about these classroom management practices and strategies by taking part in our professional development courses and workshops.

Margaret Berry Wilson is the author of several books, including: The Language of Learning, Doing Science in Morning Meeting (coauthored with Lara Webb), Interactive Modeling, and Teasing, Tattling, Defiance & More.