When used calmly, consistently, and respectfully, Responsive Classroom time-out can be a valuable strategy for helping students develop self-control while keeping the classroom calm, safe, and orderly.

When used calmly, consistently, and respectfully, Responsive Classroom time-out can be a valuable strategy for helping students develop self-control while keeping the classroom calm, safe, and orderly.

Santiago is at the interactive whiteboard, showing the class his solution to a math problem the teacher challenged them with. Everyone is paying attention except Claire, who repeatedly and loudly bangs her feet together. Her teacher reads confusion and tension in her scrunched-up face.

“Time-out,” the teacher says quietly to Claire.

As she and her classmates learned to do in the early weeks of school, Claire gets up and goes to a chair a few feet away but still within earshot of the group. She takes some deep breaths but continues to seem tense. Then she remembers the additional calming techniques her teacher taught the class and picks up a soft ball stored in a small box nearby. As she squeezes the ball, she relaxes and returns her attention to Santiago’s math demonstration. At a nod from the teacher, Claire returns to the circle, in time for questions and comments about Santiago’s solution.

Time-out in a Responsive Classroom is a positive, respectful, and supportive teaching strategy used to help a child who is just beginning to lose self-control to regain it so they can do their best learning. An equally important goal of Responsive Classroom time-out is to allow the group’s work to continue when a student is misbehaving or upset. Giving that child some space from the scene of action where they can regroup while still seeing and hearing what the class is doing accomplishes both of these goals.

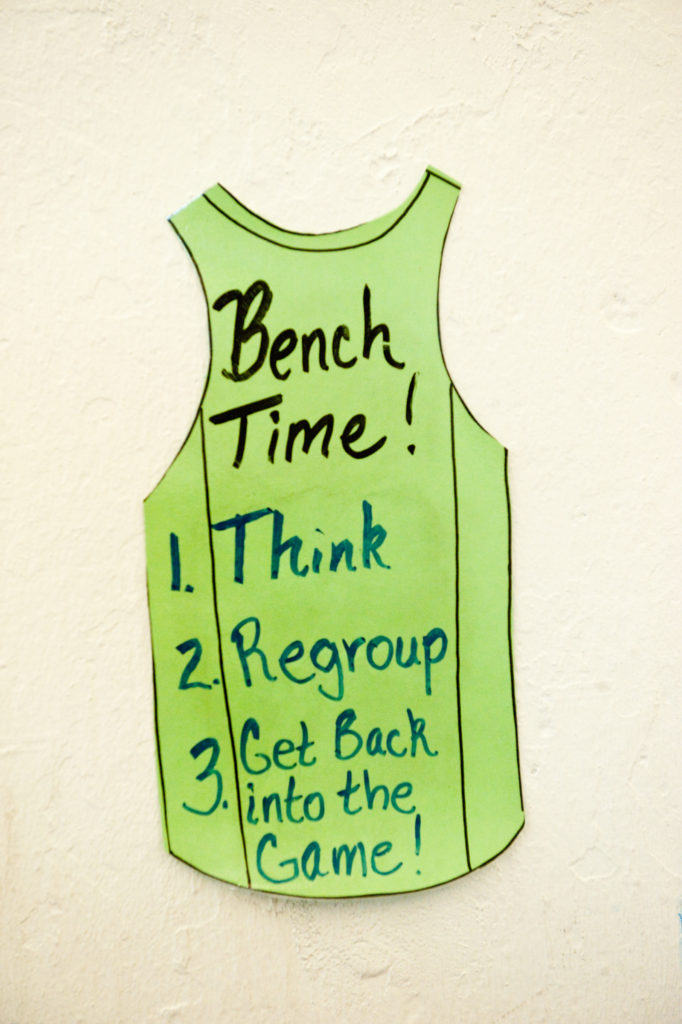

Responsive Classroom teachers carefully introduce time-out early in the year. They often call it “Take a Break” (as it’s referred to hereafter in this article), “Rest and Return,” or a similar term that separates it from the negative associations some students may have formed from prior experience. And they use it judiciously, as just one of several strategies that can help children stay focused on learning and working productively with others.

The following guidelines will help you use Take a Break as a positive and supportive teaching strategy. At the end of the article, you’ll find resources that go into greater depth.

Rather than only responding when children struggle, it’s important that we first establish with children the expectations for behavior and then take the time to teach them how to translate those expectations into action in different classroom and school situations. Interactive Modeling is one Responsive Classroom practice for teaching such skills.

Many children have experienced punitive uses of time-out in the past. It’s important, therefore, to explain clearly that its purpose in your classroom is not to punish anyone but rather to help students restore the mental focus and emotional control needed for efficient learning. Let children know that sometimes they might decide for themselves that they need a break, in which case they can go to the break spot on their own. This can further erase any stigma associated with Take a Break.

It’s best to have one or two designated Take a Break places—chairs, cushions, or beanbags that are neither isolated nor in the thick of activity. You want to give children the separation they need to calm and refocus themselves, yet enable them to keep track of what’s going on in the classroom so they can rejoin the work when they return. To keep students safe while they’re in a break, make sure you can see the spot or spots they go to from anywhere in the room.

Early in the school year is the time to talk about, model, and let students practice how to use Take a Break. Be sure your teaching covers these key points:

Don’t wait until a child’s frustration or misbehavior escalates. It’s easier for children to recover from a smaller than a bigger upset or distraction. Using Take a Break early also helps preserve your feelings of empathy toward children. It can be hard to have empathy when, for example, a child has become aggressive.

Of course, to use Take a Break early, we must observe children well so that we catch signals indicating they’re about to lose control. They may make negative remarks, pick and poke, furrow their brows as their faces flush, or crumple up their papers. Learning students’ early signs of losing self-control will help you respond proactively.

Knowing the children you teach will help you decide if Take a Break is the strategy most likely to help a particular child. For instance, using Take a Break for fidgeting may be inappropriate if what a child needs is more physical activity or a different seating arrangement (to sit in a chair instead of on the floor, for example). For other children, a break may be just what’s needed to get the fidgets under control.

Also, a child who has completely lost control is beyond Take a Break. In these cases, you need a strategy that may involve the principal, a guidance counselor, or other support staff.

Finally, if you repeatedly send a child to Take a Break without seeing any improvement in behavior or frustration tolerance, or if a child crumples or becomes extremely distraught at even one use of Take a Break, more than likely the child needs a different strategy. Seek help from colleagues, parents, and counselors, and consider other problem-solving strategies.

If you’ve taught Take a Break well, saying a simple “Take a break” may be all that’s needed in the moment. Even better, teach and use visual signals for going and coming back. This avoids drawing attention to the child or distracting classmates.

Never negotiate with the student in the moment. Remember that an important purpose of Take a Break is to allow the group’s work to continue when a student is misbehaving or upset. Discussing the situation with the student will only disrupt the group further. Moreover, a student who needs a break may not be in a frame of mind to discuss the situation reasonably. However, when you introduce Take a Break, it’s important to assure students that they can always talk with you about the situation later.

Responsive Classroom Take a Break is a broadly useful strategy for helping children collect themselves, whether that takes the form of loudly acting out or silently hitting a personal wall of frustration that’s impeding their learning.

When you teach Take a Break, it’s important to let children know that because it’s useful in so many situations, just about all of them will have the opportunity to experience it at one time or another. Getting that message generally helps children accept using the strategy when they need it.

In the article “Time-Out & Teaching Self-Regulation,” Responsive Classroom consultant Tracy Mercier tells the story of Martin, an easily frustrated child whose frustration often mushroomed into angry outbursts. Tracy shows how Take a Break can be not only a teacher tool for directing children, but a tool children use themselves to regulate their own emotions and behaviors. With Tracy’s help, Martin eventually learned to monitor his own internal states so that he could, without any intervention from Tracy, productively take a break as soon as he felt himself getting too upset to learn and work well with classmates.

Many teachers set up a “buddy system” for times when a student refuses to take a break, continues to be disruptive or upset while there, or continues to struggle after coming back. The teacher then has the child take a break in another teacher’s room. This prevents the situation from escalating into a power struggle and enables the teacher to go on teaching the class. See the article “Buddy Teachers: Lending a Hand to Keep Time-out Positive and Productive” to learn about the buddy teacher strategy.

Calming oneself, controlling impulses, and consistently following the rules of the group are tough skills to master. But they’re essential for the smooth functioning of a learning community, as well as for each student’s personal growth. Take a Break—Responsive Classroom time-out—is one strategy teachers can use to help children develop these skills while ensuring everyone’s safety and keeping the learning going full steam ahead.