In the fall of 2003, our school community had identified ensuring a positive school climate as a top priority. We wanted to devise consistent, schoolwide disciplinary policies to help children follow schoolwide rules. These policies would apply to all behavior, whether occurring within or beyond the classroom. Next, we needed to help the children create the school- wide rules. Then we had to help them learn what following those rules would look like, feel like, and sound like. What, for example, does a common rule such as “Be kind” look, feel, and sound like for children sharing the lunchroom space?

All of these steps were integral to improving the school climate. The step that this article will focus on is the creation of the schoolwide rules, undertaken in fall 2004, the second year of our project. Students, parents, teachers, counselor, and principal worked hard together to create a Sheffield “Constitution”—a set of schoolwide behavioral guidelines distilled from separate sets of classroom rules. As our second year progressed, we began to see some positive results: Our use of common teacher and student language about behavior and rules, the emphasis on teacher modeling, and a great deal of practice in living our constitution all helped make the school climate more peaceful and productive.

Schools will find many ways to do the hard work of developing schoolwide rules, depending on the ages and needs of their students. Here is what the process looked like at Sheffield.

We began our work formally in January 2004. We adults (principal, counselor, teachers, support staff, and parents) asked ourselves two key questions about our readiness to help the children formulate and follow schoolwide rules:

In January 2004, a task force made up of teachers, other staff, and parents began exploring what a schoolwide discipline plan would look like. The task force set up discussions with the entire staff and surveyed parents, staff, and the whole student body (over 270 students). They received written responses from 243 students, 104 parents, and 43 out of 55 staff. The active involvement of so many members of the school community was important, given the size and complexity of the project.

One outcome of the discussions was the creation of a set of disciplinary guidelines for handling children’s behavior problems anywhere in the school. The guidelines were eventually included in the parent-student school handbook, which we sent home with students in September of the 2004/05 school year. These guidelines included “Steps to Self-Control” that would help children get back on track when they were having trouble following classroom or schoolwide rules (see below).

from the Sheffield Elementary School Parent–Student Handbook

The following three steps usually help children manage their behavior in both classroom and nonclassroom areas. When these steps are not enough, the handbook goes on to discuss keeping students after school for social skills tutoring with the principal or extra homework help. Suspension (either in or out of school, depending upon child and family needs), is still used for serious misconduct.

When children begin to lose control, teachers remind them of the rules and, if necessary, calmly and concisely redirect their actions. For example, to a child disrupting another student’s work, a teacher might say, “Take your work to that table, please.”

If children continually choose to ignore or are so upset that they cannot follow the rules, they need a few minutes in a safe place to cool down. This “Take-A-Break” area is within the children’s classroom. Sometimes a buddy teacher’s classroom is used as a next step.

If children continue acting out, they need to spend more time in a quiet place. In our Peace Room, an adult helps upset students focus on structured problem-solving without distractions, do assigned classroom work, and interrupt a pattern of nonproductive behavior. They stay in the Peace Room until they show their readiness to be welcomed back into the classroom.

Teachers and staff adapt these steps for use in the lunchroom, hallways, and other school spaces. For example, a child who is becoming too noisy at lunch may be told to go for a calming-down break in the Peace Room, which is right across the hall.

Any nearby adult member of the school community will take responsibility for guiding children through these steps to self-control.

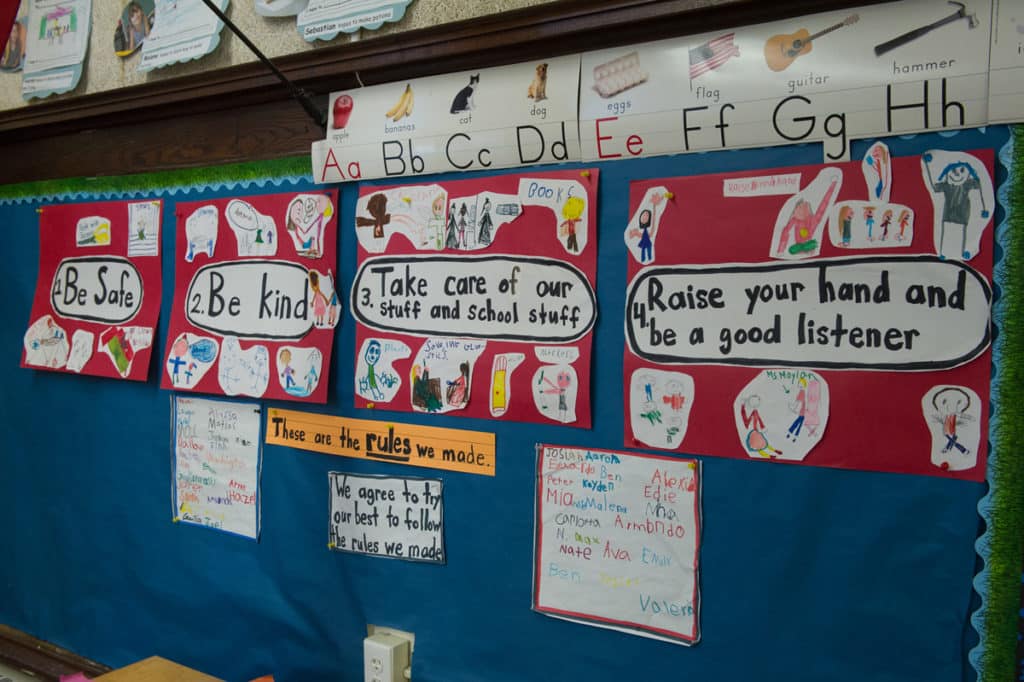

At the start of the 2004/05 school year, each class had created their own classroom rules (see below). By late September, the classes had been learning and living with those rules for several weeks.

In classrooms using the Responsive Classroom approach, teachers work with the children to create the classroom rules. Generated from students’ ideas, these rules set limits in a way that fosters group ownership and self-discipline. Rule creation takes place in the early weeks of school. Here is what the process typically looks like.

Teachers find over and over that this investment of time and effort is well worth the payoff of calm, productive, and joyful classrooms.

At the end of September 2004, after fourteen months of working hard together, we had classroom rules and a set of clear disciplinary policies in place. Finally, we were ready for the children to consider what safe, respectful behavior would look like inside and outside the classroom. It was time to create the Sheffield Constitution.

To enhance academic learning as the children worked on their schoolwide rules, we decided to guide them through the same sort of democratic process that resulted in the creation of the U.S. Constitution in 1787. In the classrooms, teachers noted that our school’s rule-making process was similar to the one by which our nation’s founders had created the most important laws of our country. Social skills were bolstered as children from all classes and grades worked together.

Each of the school’s fourteen classes chose two delegates to represent them at a grade-level mini-convention. The job of the delegates at each grade-level mini-convention was to discuss all the classroom rules for their grade and select three to five upon which all could agree. We felt that as an important part of the students’ learning, they should have some say in how they would arrive at their grade-level rules, as long as their method was fair and respectful. Some delegates voted rule by rule for inclusion or exclusion. Others grouped similar rules so that they could more easily decide among them. One grade felt it important to include at least one rule from each classroom.

The mini-convention delegates talked about what the words they were using meant—words such as “respect” and “responsibility.” One group of students said that respect meant “listen when the teacher’s talking; don’t talk back.” Another group said that respect meant “be nice to everybody.” Students also discussed what it would look, sound, and feel like to follow the rules they were crafting. “If Rebecca were being kind to Simon during math,” the adults asked, “what might she say if he made a mistake?” One student said, “She could say, ‘How did you get that answer, Simon?’” Another student suggested that Rebecca could say, “I have another idea, Simon. Would you like to hear it?”

By the end of the mini-convention, we had four sets of three to five rules, one set for each of the grades in our school. We were ready for the next step.

Before adjourning, the classroom delegates decided which two delegates would represent their whole grade at the Sheffield Constitutional Convention. On September 27, 2004, these eight grade-level delegates, along with the school counselor and principal, set off for “Philadelphia”—the superintendent’s conference room on the other side of our complex. After a formal greeting and words of encouragement from superintendent Sue Gee, the delegates got down to the business of transforming four sets of grade-level rules (a total of approximately sixteen rules) into one set of three to five schoolwide rules.

Taking their responsibility quite seriously, the delegates reviewed and discussed and struggled to find a way to reduce the many rules down to just three to five. They tried choosing rules from the various class posters. They tried categorizing and grouping rules that were similar. We (their principal and counselor, the only adults present) offered suggestions and gentle guidance. But the first hour passed and the delegates had not agreed on a single rule.

At this point, we offered the delegates a challenge: We would leave the room and return in five to ten minutes. The delegates’ task: Agree on the most important rule and write it on the chart paper. We checked in at the end of five minutes and were told “Not yet!” We were worried: Would this work? Was the task too big? Would the children be able to come up with even that first rule? After another ten nerve-wracking minutes, we were welcomed back into the room. There on the paper was one word in big, bold letters: ENJOY!

The delegates were excited. We adults were pleasantly surprised by the concise and powerful first rule. But we were still worried: Would the children finish the rest of the rule-making successfully? We were politely told to “go away again.” The students would work on the second rule and tell us when they were ready. We waited in the hall. Each time we checked, we were told “Not yet!” As school dismissal time approached, we began to wonder if the task could be completed on time.

Finally, we were signaled back in. Expecting to see only rule two added below rule one, we were delighted to see instead five rules and a very satisfied-looking group of delegates. After about an hour and a half of serious deliberation, fourteen sets of rules crafted by over 270 students were now represented by one set of proposed schoolwide rules: Following “Enjoy!”, we saw “Respect everyone and everything around you, Speak kindly, Be helpful and responsible, Take care of classrooms and school property.” The delegates were now ready to present their work to the school community.

Sheffield Rules

On October 6, 2004, the whole student body assembled in the auditorium along with teachers, parents, principal, counselor, and official guests. All the rules from which the schoolwide rules had been distilled—the fourteen classroom rules posters and the four sets of grade-level rules—were displayed at the front of the auditorium.

Mr. White, the school counselor, asked all the students, teachers, and other school staff to stand. “Everyone you see standing here,” he said, “participated in creating the classroom rules that are the foundation for the schoolwide rules we will ratify today.” The whole auditorium rang with enthusiastic applause. Mr. White then heightened the excitement by asking everyone to be seated except for the two delegates from each of the fourteen classrooms. After another big round of applause, Mr. White asked these twenty-eight students to be seated and turned everyone’s attention to the stage, where the eight grade-level delegates sat with the superintendent of schools, school committee chair, fire and police chiefs, town select board, and other local officials. Behind them hung a giant poster of the Sheffield Rules, which had been commercially produced to emphasize the importance of the occasion.

Mr. White described the long and careful process these eight delegates had followed to distill the schoolwide rules from so many sets of classroom rules. Then he invited the delegates to explain each schoolwide rule. “Rule one,” they said. “Enjoy. That means enjoy learning, enjoy your classmates, enjoy your teachers, enjoy recess, enjoy school.” In similar fashion, they explained each of the remaining four rules. When they finished, the rules were affirmed by voice vote and a stirring standing ovation. Invited guests congratulated the delegates on their accomplishment. The guests also reminded all of the students that for the work they had done to be meaningful, the whole school community (children and adults) would need to help one another learn and live by the constitution in the months ahead.

After the ratification ceremony, smaller versions of the Sheffield Rules poster were given to staff for posting in classrooms and in the hallways, lunchroom, library, and other common school areas. In the classrooms, teachers helped children see how the Sheffield Rules were similar to their own classrooms rules. For example, a teacher might say, “The Sheffield Rules are the ones we follow when we’re outside our classroom. They have the same ideas as our classroom rules, although some of the words are different.” The teacher might then guide the children through a comparison of words and ideas to help them relate the two sets of rules.

Parents also received copies of the schoolwide rules with reminders of which pages in the parent-student school handbook would apply when any of these rules was broken.

We know our schoolwide rules need to belong not just to the students present in our constitutional year, but to all the students following them. That means discussion, modeling, and practice of the rules as we welcome new children each year. It also means ongoing communication among all the adults of the school community. Sharing insights and observations is the best way to know if the rules are helping us meet our hopes and dreams for all the children.

Creating schoolwide rules and disciplinary policies helped Sheffield School take a huge step toward resolving concerns about school climate. Engaging all of the children in the rule-setting process helped them take ownership of the rules. Engaging all of the adults emphasized for the children the significance of their work. Together, we are creating a calmer, happier place for learning.

Kevin B. White, MEd, has been a school counselor at Sheffield Elementary School in Turners Falls, MA, since 1991. Also a teacher and administrator, he is currently pursuing licensure as a guidance director. For the past four years, Kevin has supervised school counseling interns at Sheffield in partnership with the School Counselor Education Program at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Chip Wood is principal of Sheffield Elementary School and a co-founder of Northeast Foundation for Children. He is the author of Yardsticks: Children in the Classroom Ages 4–14 and has authored or co-authored several other books and articles on education, child development, and the Responsive Classroom approach to teaching.