Public discipline systems—like moving clothespins along a colored card, writing names on the board, or the stoplight system—can certainly be appealing. Some days can feel as if they’re spent just disciplining. Public discipline systems promise to turn that around by decreasing misbehavior and increasing motivation through the use of visual feedback. The phrase often heard during a conversation about public discipline systems is that “children know exactly where they stand.”

And these systems do work, but only in the short-term. At first, students are in awe of the novelty. They initially like the idea of being able to earn points or have their clothespin on the blue card, and they’re eager to please their teacher by demonstrating their absolute best behavior; they want to be good even if they are unclear about what that means.

However, public discipline systems quickly lose their novelty and cease working. Children who continuously lose points, are placed on red, or have their name written on the board are publicly humiliated. For many students, that experience increases the negative behavior. Some children who end up consistently on green or blue do not enjoy being pointed out. Public recognition of their good behavior embarrasses them. Other students find it difficult to maintain the illusive standard of good behavior and will lie or cheat to keep their points or stay on green.

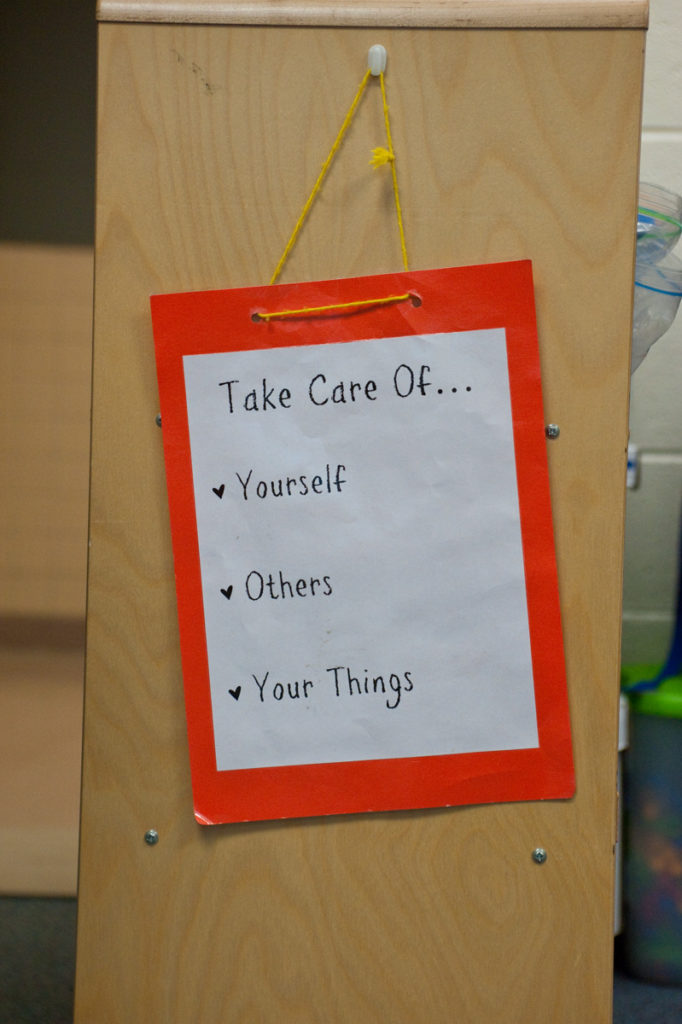

Teachers who use public discipline systems do so because they want to recognize positive behavior and respond to misbehavior. They want to effectively manage their classroom so that all children will be able to learn. But there are ways to do this without causing the problems associated with public discipline systems:

Use reinforcing language when a student behaves positively. For example, when a student who usually argues during Four Square plays one round argument free, her teacher might say, “Sabrina, when someone called you out you went to the back of the line right away.” The words, along with the teacher’s friendly and encouraging demeanor, tell Sabrina exactly what she did that was helpful and what she should keep doing.

Use reminding language when you notice a student just starting to go off course. For example, when a student is beginning to struggle with listening, you can say quietly and matter-of-factly, “Remember what we said about being a respectful partner.”

Use nonverbal cues when a child behaves in a problematic way. For example, put your finger to your lips as a silent reminder to listen or shake your head to signal a student to wait until you’re finished giving directions before reaching for the supplies. Even simply moving to stand next to a child who’s misbehaving will often restore positive behavior quickly.

Use redirecting language when nonverbal cues aren’t enough (or you sense the student is beyond being able to take in such cues). For example, Jed is running across the classroom with a pair of scissors. You say, kindly but very firmly, “Jed, stop now. Put the scissors down.” Once the unsafe behavior has stopped and you and Jed are both calm, you discuss the unsafe behavior he chose and the safe behavior you expect.

Sometimes students need more than a cue or a redirection to correct their behavior. In that case, logical consequences can do the job. Unlike punishments or public demerits, logical consequences help children connect their behavior to its effects and repair any damage that behavior may have caused. Logical consequences are also respectful of the child. Examples: If a student fools around and spills water all over the bathroom, a logical consequence might be that he cleans up the water. Or if a child accidentally deletes her partner’s computer work, she needs to find a way to help her partner recreate the work. If a student is losing self-control during group work, you may direct her to take a positive time-out, a break from the action so she can regroup mentally and emotionally.

So whenever you feel tempted to turn to a public discipline system —for example, during long stretches of indoor recess, before or after holidays and vacations, or as the school year closes—remember that this quick-fix will not result in long-term behavioral changes. In contrast, using Responsive Classroom practices can give you the long-term improvement you’re looking for: teacher language helps children know precisely what they’re doing well and what behavior they should continue; using logical consequences helps children repair and learn from their mistakes; both of these practices help children create a repertoire of positive behaviors to call on in the future. And developing children’s ability to select positive behaviors is what discipline is really all about.