One of the most valuable things we can teach students is how to assert themselves in respectful ways. In spontaneous and planned moments throughout the day, teachers can work with students to think about what they want to communicate, to examine their words, and to try new and different ways of speaking.

But who has time to let children talk, we teachers often ask, when standardized tests are upon us starting from September and many of our students are reading below grade level? Perhaps we also fear behavior problems. For many years, I thought it would be easier to keep students quiet than to negotiate a conversation, especially in the upper grades.

But when I think back on my most valuable lessons in childhood—the moments I am most proud of—they are times when I spoke up. The ability to speak up assertively and respectfully is a form of power that helps our students succeed in school and in life. If I keep the classroom silent, I’m robbing students of this power.

Despite the concerns about falling behind or, worse, inviting chaos by encouraging talk, I have found that when children know how to talk skillfully, behavior problems decrease. I do less talking and more teaching. Students learn more each day, finding new strength in their academic and social lives as they find their voices.

Here are some strategies that I’ve found helpful in coaching talk among fifth graders in two kinds of situations: spontaneous teachable moments and planned discussions.

Students’ school days are filled with moments of conflict or awkwardness that can be positively handled with the skillful use of talk. Coaching students through these times involves:

It’s the end of the day, and the class is packing their bags, talking about their after-school plans. But it’s getting too loud. I see Terrence and Laquasia talking loudly, possibly angrily, at each other. I flick the lights, signaling the class to stop, look at me, and listen up.

“It’s too loud in here. Pack-up time needs to be calmer so everyone can get organized.” I walk over to Laquasia and Terrence, who are looking upset.

“What’s happening here?” I ask.

I learn that Terrence just threw Laquasia’s coat on the floor. He says she had stepped on his and that’s why he threw hers down. Laquasia confirms the story, but neither of them knows what comes next.

“Terrence, what other way could you respond that’s respectful, but that gets your point across?”

Terrence pauses, then turns to Laquasia and says, “Oh, that’s okay, Laquasia. Don’t worry about it.” He turns back to me, as if to say, “Is that okay?”

It is not okay, because while Terrance’s response might sound respectful, it is not true to his feelings. I don’t want students to think that being respectful means avoiding your own needs and feelings.

“I’m guessing, Terrence, that it’s really not okay with you when someone steps on your coat,” I say. “Watch me for a minute. Here’s another way you could respond: ‘Laquasia, I’m really mad right now. It’s not okay for you to step all over my coat.’” In my demonstration, I make eye contact with Laquasia and use a strong voice without yelling. It’s important to teach that our body language and tone of voice are just as important as the words we use.

Turning back to Terrence, I continue, “Terrence, now you can tell Laquasia what you would like her to do if this happens again. You could start with, ‘Next time you see a coat on the floor, you could . . .’ “

Terrence repeats the prompt and finishes with two excellent suggestions: hang it back up, or bring it to him at his desk.

Children do not come to school necessarily knowing how to engage in discussions about books, ideas, or social issues. They need to be actively taught discussion skills, just as they need to be actively taught how to read, write, do math, draw, or conduct a science experiment. Some helpful strategies in this teaching include:

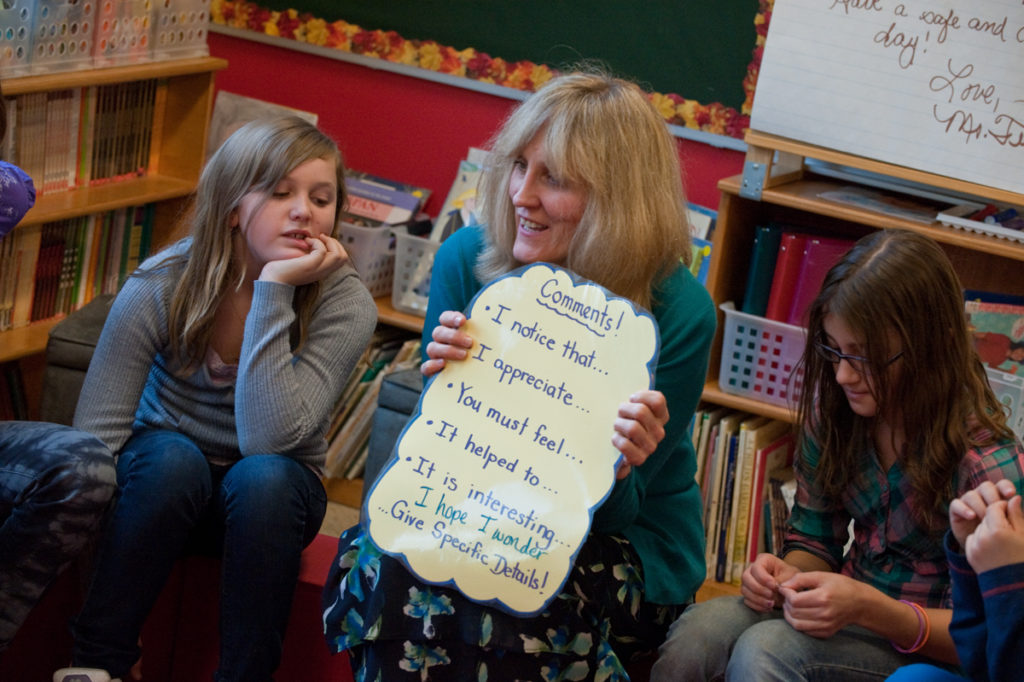

It’s the middle of the year, and the class is partway through our read-aloud of Sidewalk Story by Sharon Bell Mathus. Early in the year, we had brainstormed some constructive phrases to use in holding a book discussion. Ideas included:

We had written these phrases on a big chart and had been practicing using them. On this day, the students are sharing their thoughts about Lilly, the main character in Sidewalk Story, and her best friend Tanya.

“Usually in starting a conversation about a book, it helps to begin with an idea you’re working on or a question,” I remind the class. “Who can get us started?”

Five or six hands go up. Nica offers her idea. “I think Lilly’s mom is really mean. She’s always yelling at Lilly.”

The students think about this for a moment, and then begin to talk. “I agree, and Lilly doesn’t even deserve to be yelled at,” Michael says.

“That’s true, but I don’t think the mom’s really mean. She’s more like, worried,” Marcos responds.

So far so good. The students are listening to each other, agreeing and disagreeing respectfully, moving the discussion along.

Then, Malek makes a comment and an excited Nica responds by saying, “No, but Lilly’s mom isn’t …”

I catch Nica’s eye and gesture toward our chart of respectful discussion phrases the class agreed on. Nica starts again. “I don’t see it that way, Malek. What about…” The students pick up on the correction, but the interruption to the discussion is minimal and they continue easily.

Later in the conversation, Jeremy makes a comment that is too far from the story. “Tanya’s mom and Lilly’s mom probably had a fight or something, so that’s why they hate each other.”

There is no evidence of such a fight in the book. Seeing this as a chance to model how to handle such a situation in a discussion, I say, “I agree it could happen that the two mothers would have a fight. But I don’t remember anything in the book that says they did. Do you?”

“No, I guess not,” Jeremy says.

At this point I want the class to see that we can use talk not only to question each other’s ideas, but to build on them. So I say, “But you’re getting at something here, Jeremy. The mothers don’t fight, but they don’t help each other out. Do you have an idea about that?”

Jeremy thinks a minute, then begins to talk about how Lilly’s mom might not be helping because she doesn’t want to get her own family in trouble.

I look around the circle and remind the class, “Now would be a smart time to go inside the book and see if we can get some backup for Jeremy’s idea.” We are quiet for a minute as we think about which scenes in the book might have what we’re looking for. Jeremy sits tall, knowing the class is invested in his thinking, but also understanding that his ideas are more powerful when he expresses them accurately and without exaggeration. The class, meanwhile, has learned a way to disagree respectfully and move a discussion constructively toward more sound ideas.

Teaching students how to talk can be hard work. When our daily schedules are accounted for down to the minute, it’s hard to slow down to have these conversations. It might seem easier not to teach talk. But it’s scary to think what children would miss. We need to prepare them to be respectful and assertive in their lives, and there are bigger problems they’ll face than a couple of winter coats thrown on the floor or a sloppily constructed idea about a book. But those are good places to start. From those modest beginnings, children can learn to speak up in the world—inside and outside our classrooms.

Megan Earls taught fifth grade in New York City public schools for four years. This year, she is teaching fourth grade at PS 58 in Brooklyn. Before teaching, she worked at Fellowship of Reconciliation, leading workshops for youth on anti-racism and nonviolence theory and practice. She is particularly committed to creating a classroom where students question the way things are, imagine the way things could be, and learn to take clear, confident steps to assert themselves.

Another Teacher’s Experience: See how kindergarten teacher Eileen Mariani helps children learn through meaningful talk in Chapter 3, “Ritual and Real,” in the book Habits of Goodness.