How one teacher deals with interruptions and keeps learning running smoothly.

Picture this: My reading group is attentive and prepared for a discussion of a favorite novel. “What if Darry had called the police?” I ask, urging them to consider other possible outcomes. Jenny initiates a thoughtful reply, but Eric interrupts. “That’s crazy,” he cries, “Darry would never do that!” My first thought is that this is a triumph. Eric, a recalcitrant student, is finally excited. But Jenny is now silenced. Rather than promoting discussion, Eric’s outburst has dulled it.

Several days later, I fill in for a third grade teacher who has unexpectedly resigned. The children gather for the morning meeting—a time for greeting, sharing news, and most important, a time to set a positive tone for the day. Although I anticipate a class in the throes of a confusing transition, the constant disruptions surprise me. “Stop! You’re bothering me,” Kim blurts out. David complains loudly, “I can’t see!” A child enters the room and Julia cries, “Hi, Sheila!” I call on Jerome, but Michael angrily interjects, “Hey, I said that first.” Brian pokes him and giggles, “But that’s not the right answer!”

Sound familiar? As teachers, we strive to promote student participation. But when a child’s involvement or eagerness is impulsive and uncontrolled, it interferes with learning and communication. In both of these situations, I only covered a fraction of the material I’d planned and the cooperative spirit I’d hoped to infuse was squelched.

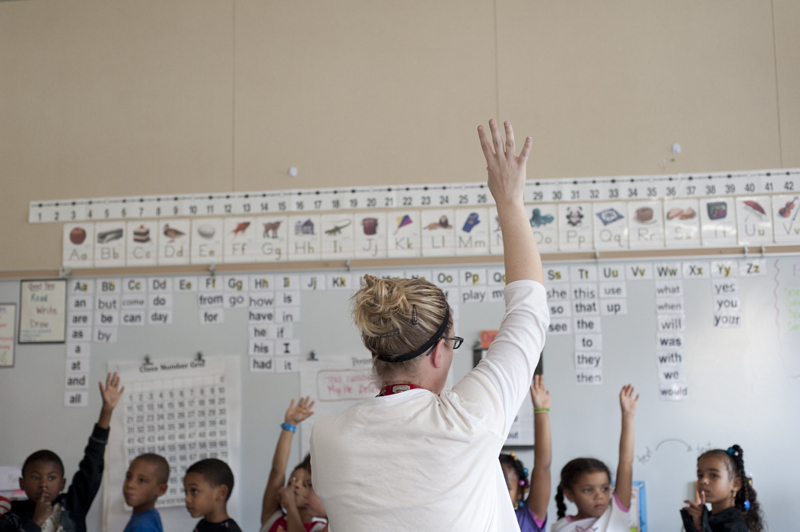

We cannot assume that children know what it means to participate productively. Yet effective group communication skills are of great import for all ages—from pre-school circle times to staff meetings, from reading groups to field trips, from lunch time conversation to our all-school assemblies. They are an integral and integrated aspect of our social and academic curriculum. They are social skills we must teach.

Below are strategies for teaching children to communicate effectively and respectfully, strategies which I used in the above “case of the blurts.”

Give children a sense of purpose and a vision of where you are headed.

In the case of the third graders’ morning meeting, I began the next day by saying: “I know this is a hard time for you, but I want us to have morning meetings that are interesting, fun and important for everyone. To do that, we will need to have important participation. Can anyone tell me what they think I mean by ‘important participation?'” (With older children I often use the term “honest discussions.”)

For Eric, I scheduled a private conference with him. I acknowledged his input in the discussion and shared my pride in this academic growth. Then I explained the importance of hearing other points of view and outlined my goals for the reading group. I also shared my own personal struggle to be more patient and not blurt out my ideas. This laid the groundwork for connecting my goals for the group with Eric’s behavior. I asked him to work on waiting, raising his hand, and listening to others.

Once you’ve outlined them, make sure you reinforce them.

In the above case, I asked students to help me define the term “important participation.” I told them the goal was to listen and speak so that we all learned from one another. Together we generated simple rules of respect for meetings: raising hands, not interrupting, not making put-downs.

I ask my students, “If you have a good idea, how can you share it?” I have the children demonstrate how and when to raise one’s hand without distracting others or waving excitedly and calling “I know! I know!” I also ask the children to be on the lookout for clues for when they should raise their hand.

Provide as many alternatives to blurting out as possible and clue kids in to signals that help them know when, for example, to raise their hand.

Having the children come up with ideas for solving the communications problems will increase their investment and chances for success the next time around.

I asked groups of sixth graders to plan a diorama of a Colonial village. They needed to decide—as a group—the desired structure, characters, materials, and scale. One group was so busy arguing with everyone talking at once that after 15 minutes—and a few reminders and interventions from me—nothing was accomplished. I said to them, “I am going to send you all back to your seats. When you each have a plan for how you will be able to work productively, you may continue.”

I think of a particular third grade group which was excited and excitable. Group lessons were littered with interruptions and distractions. I challenged the group to get through a 30-minute lesson with no more than one interruption. The challenge was posed as a contest rather than a threat. There would be a celebration if they succeeded. It is key to structure such a challenge as a group endeavor so that it doesn’t generate a backlash toward an individual, such as “You made us lose!” Their first task was just to notice and record blurts and interruptions. They were surprised at the number and the variations of the interruptions—and at the realization that everyone blurts out at some time or another.

Children learn to blurt out what’s on their minds. Sometimes they learn to do so because we teach it, and sometimes they learn it because we fail to teach them how not to blurt. If you know why it happens, you can better decide how to respond. The action you take will vary depending upon the root of the problem. Here are some causes for this behavior.

Ruth Sidney Charney is a co-founder of the Center for Responsive Schools and author of Teaching Children to Care.