On a winter afternoon, a group of third graders has settled down for a class discussion. Their teacher, Nancy Kovacic, holds the book the children made last fall—pictures and words embodying their social and academic aspirations for the year. “Who remembers,” she asks, “way back to September when we wrote about our Hopes and Goals?” Eight hands shoot up.

On a winter afternoon, a group of third graders has settled down for a class discussion. Their teacher, Nancy Kovacic, holds the book the children made last fall—pictures and words embodying their social and academic aspirations for the year. “Who remembers,” she asks, “way back to September when we wrote about our Hopes and Goals?” Eight hands shoot up.

“Stand if you remember your Hopes and Goals,” she adds. The students hesitate. One child stands and then quickly sits back down. Seven brave the challenge. As they take turns recalling their Hopes and Goals, memories—for some classmates rather vague—begin to surface.

Nancy, a teacher at Coleytown Elementary School in Westport, Connecticut, is helping the children revisit their early efforts to build a safe, caring, and joyful learning community. It’s an important midyear opportunity that helps the children see the progress they’ve made while setting the tone for productive learning during the remainder of the year. Here’s how Nancy goes about this process.

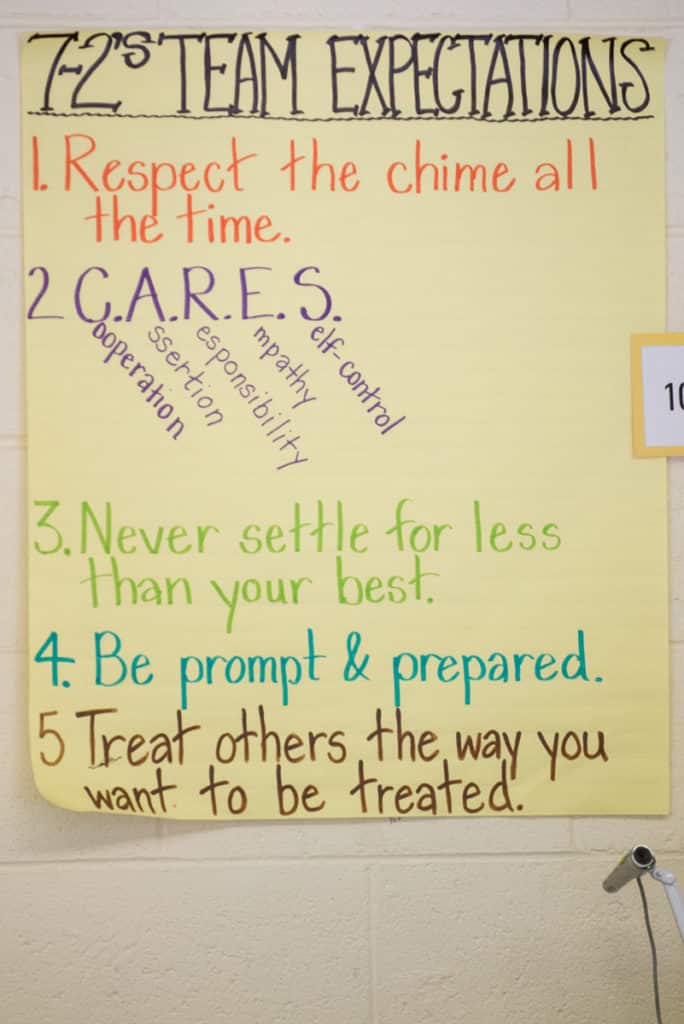

Nancy and the students spent their first six weeks together intently building their classroom community. First, the children articulated their Hopes and Goals for their year’s learning (or “Hopes and Dreams,” as many who use the Responsive Classroom approach call them). They named things from learning multiplication to making new friends to learning to write script. Next, each child created an illustration of her/his hope, with accompanying text, for a class book. Then the children helped create classroom rules—which this class calls “Agreements”—for how they would behave so that everyone could achieve their Hopes and Goals. Their Agreements were to:

Finally, the children crafted a poster of their Agreements and hung it from the ceiling—a daily reminder of how they want their classroom to be.

Nancy sees as top priorities the Hopes and Goals expressed by the students and the classroom rules those Hopes and Goals give rise to. Although Nancy recognizes the need to measure children’s content and skill learning, she wants her students to be accountable for more than just their ability to complete objective tests. She finds that articulating Hopes and Goals at the start of school helps the children connect personally to the year’s learning. And the Agreements the students help create are especially important: They remind children of the social and ethical behaviors that enable everyone to learn.

From the start, Nancy has taught and helped the children practice the behaviors embodied in their Agreements. By midyear, though, she knows that memories may need jogging. It’s been a busy four months. Holidays, snow days, early dismissals, mandated curriculum, and standardized testing are among the many things that have claimed class time and attention.

Still, Nancy makes time to keep social and ethical development at the forefront of classroom life. She believes that the learning experience is more joyful when teachers take time to teach and reinforce caring, cooperation, kindness, and self-control. Revisiting Hopes and Goals is one way to reaffirm those values.

As Nancy guides the children through their midyear revisiting, she follows the same order of teaching she used in September—Hopes and Goals first, Agreements second. This reminds the children that their Agreements are there to help them achieve their learning goals.

With Nancy’s help and with their illustrated book to jog their memories, the children one by one remember their Hopes and Goals from early fall. Each child reads her/his entry in the book aloud.

Then Nancy guides the children in thinking about their progress in achieving their goals. “For us to think more about our Hopes and Goals,” she says, “it might help to remember some things we’ve done this year to show our growth.” More digging for memories. An animated discussion ensues about class activities. Nancy probes gently, asking, “What did this activity show about your learning?” or “What was the purpose of that?”

Making new friends was a big September concern. Several children note that Greetings and Activities during Morning Meetings have helped them learn about each other. Another child mentions that having free choice for indoor recess has helped him make new friends. Book clubs, says one child, have been a way to get to know others, work together, and improve reading. Other children note that hands-on activities and Academic Choice opportunities have helped them learn. Children cite their well-worn writing books as evidence of learning cursive, a popular hope when school started.

Nancy now helps the students think about their learning for the rest of the year. She asks for a student to help model how to go about this reflection. Jake volunteers.

“Jake, what was your hope last fall?” Nancy asks.

“Writing script and multiplication,” Jake answers enthusiastically.

“Tell me what you’ve done to help yourself accomplish those goals.”

Jake hesitates, thinking. “I’ve finished all the pages so far in my cursive book.”

“Are there any letters you need to practice?”

More thinking. “Yes. N and S. I practice at home, too,” Jake answers proudly.

“We haven’t gotten to multiplication yet. Do you think you’ll keep this goal?”

“Yes, ‘cause I still want to learn multiplication and division.”

“Sounds like you’re ready to revise your goal.”

“What’s ‘revise’ mean?”

“Change it a bit from what it was. You can decide if you want to keep cursive. Maybe you want to add division.”

Jake ponders Nancy’s suggestions as she returns the personal surveys the students filled out in September. Among other things, the children recorded on these surveys one big thing they hoped to learn in third grade. Now they’ll share their surveys with a partner. Then they’ll do an individual paper-and-pencil worksheet to help them make decisions about their learning for the second half of the year: What have they already done to achieve their fall hope? What might they still want to do? And will they keep, revise, or replace that hope?

The children go right to work. In fifteen minutes, Nancy rings a chime to signal for attention. The buzz in the room quiets. “Why is it important,” Nancy asks, “for us to think about our Hopes and Goals?” She is ready to guide the children into a discussion of their classroom Agreements.

The children offer quick and telling responses to Nancy’s question. “It’s so you can try to get better,” says one child. Another offers, “So that you know what you want to accomplish. You’re not just fooling around with your friends.” A third says, “So the teacher knows what to teach you.”

Nancy can see exactly what’s on the children’s minds: They want to get better at their schoolwork, accomplish things without distractions, and have a teacher who honors their choices. “These ideas,” says Nancy, “make me think of the Agreements we made last fall so that each of us could work on achieving our goals for this year.” She directs the class’s attention to the hanging display. As the children read aloud “Treat others the way you want to be treated,” Nancy asks, “Do you think that’s happening in our classroom?”

“I’ve seen people stand up for others,” one child reports.

“Can you give a specific example?” Nancy prompts.

“At lunch Eliza sits with people who might be alone.”

Nancy probes further. “Do you think we still need to work on any of our Agreements?”

A student mentions taking care of classroom materials. “Sometimes,” she says, “the markers get mixed up and you can’t find the one you need.”

As the discussion progresses, a student, quiet until now, raises a hand. She makes a comment about inclusion. “If people aren’t letting us play or work on the computer or something like that, Mrs. Kovacic makes sure we get to join.” She’s clearly welcomed her teacher’s intervention over the past months. Many students now agree they’ve felt excluded at one time or another. The discussion moves on to ways to consistently include everyone.

For Nancy, the discussion has confirmed that certain classroom practices—hands-on activities, Academic Choice, reading partnerships—do help the children learn. She sees that the children could do a better job with classroom materials. Plus, she’s reminded of how important social safety is to her students. Without it, learning is more difficult. “Exclusion undercurrents seemed to be developing,” Nancy notes. “I might not have noticed if we hadn’t had our January discussion.” Now she could plan to keep an attentive eye on this important issue.

Nancy closes with the simple statement, “I think we have a really good idea of what we hope to achieve for the rest of this year and how we can go about meeting our goals.”

In the hustle and bustle of classroom life, students may lose sight of their hopes and accomplishments. They may forget how their classroom rules enable everyone to learn. Taking time for a reflective discussion midyear gives them an important opportunity to refocus and practice. That helps ready everyone for a second half of the year filled with joyful learning.

Michele Cunningham is a certified Responsive Classroom consulting teacher and a program supervisor for the Collaborative Teacher Education Program at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Previously, she taught for twelve years in Westport, Connecticut, where she implemented the Responsive Classroom approach alongside Nancy Kovacic.