The fifth graders and their teacher, Mr. Lomax, sit in a circle. In front of Mr. Lomax is an array of five dictionaries. The largest dictionary has a worn leather cover and looks well-used. The rest of the dictionaries come in all sizes and shapes—two paperbacks, a bright red hardcover, and another hardcover that’s a sedate gray.

“Today we’re going to explore dictionaries,” Mr. Lomax says. “I love dictionaries. I always learn something new when I flip one open.” He picks up the old dictionary and gently touches its cover. “Now I know you’re all familiar with dictionaries. What have you used them for so far?”

A few hands shoot up.

“I look up words to see if I’ve spelled them right.”

“Whenever I ask my mom what a word means, she tells me to look it up.”

“We used a Spanish dictionary a lot last summer when we went to Puerto Rico.”

So begins a Guided Discovery of dictionaries.

Guided Discovery is a teaching strategy used to introduce materials in the classroom. The primary goal of Guided Discovery is to generate interest and excitement about classroom resources and help children explore their possible uses. Guided Discovery also provides opportunities to introduce vocabulary, assess children’s prior knowledge, and teach responsible use and care of materials.

A Guided Discovery can take as little as fifteen or twenty minutes. But the interest and excitement that are generated and the skills that children practice support academic learning throughout the day.

A Guided Discovery has five steps and usually takes about twenty minutes. Here’s what those steps look like in action:

Second grade teacher Ms. Martell holds a covered plastic box. “I have some wonderful tools in this box,” she says as she shakes the box. “They come in many colors and you use them to draw. What could they be?”

One of the goals of step one is to get children interested in the material. One way teachers do this—particularly with younger children—is to create a mystery. This engages children’s thinking and helps them see familiar materials with fresh eyes.

But materials don’t always need to be hidden inside packages, and introductions don’t always need to take the form of mysteries. The teacher’s tone of voice and the way s/he holds the material can catch children’s attention. In the opening vignette, the teacher’s excitement about the dictionaries and the reverence with which he handled the old dictionary helped get the children interested in learning more about the potential of a familiar tool.

Another goal of step one is to build a common knowledge base. To do this, teachers use open-ended questions that encourage children to think about their past experiences with the material and to share current observations. Questions such as “How have you used dictionaries so far?”, “What might be in this box? What are your clues?”, “What do you know about markers?”, and “Look closely at your ruler. What’s one thing you notice?” are all examples of open-ended questions.

Open-ended questions are at the heart of Guided Discovery, occurring in every step. When teachers ask an open-ended question, they are looking for a reasoned, relevant response rather than one “correct” answer. By listening without judgment to a range of answers, the teacher says “You have valuable experience and ideas that we want to hear about.”

“We’re all going to get a chance to work with the modeling clay today,” Ms. Wilson says to the circle of K–1 students. “First, we want to think about some ways to shape it. Who has an idea to share?” Students call out their ideas:

“Make a ball.”

“Flatten it into a pancake.”

“Make a long, skinny snake.”

“What a great start!” Ms. Wilson says when there is a pause. “I wonder if we can come up with two more ideas.”

“Make a letter.”

“Make a number.”

In step two, the teacher invites children to think through how to use the material. Ms. Wilson begins with an open-ended question to get children thinking. When the brainstorming falters, she challenges the students to go beyond their first ideas. She uses the phrase “I wonder” so that the challenge seems fun rather than stressful.

After the children name ideas for using the material, the teacher invites them to model some of the uses:

“Alexis, you suggested making a ball,” Ms. Wilson says. “Will you show us how you do that?”

Alexis sits down next to Ms. Wilson, takes the small piece of clay that Ms. Wilson hands her, and carefully rolls and pats it into a ball.

While she works, Ms. Wilson asks the rest of the class, “What do you notice about how Alexis is making a ball?”

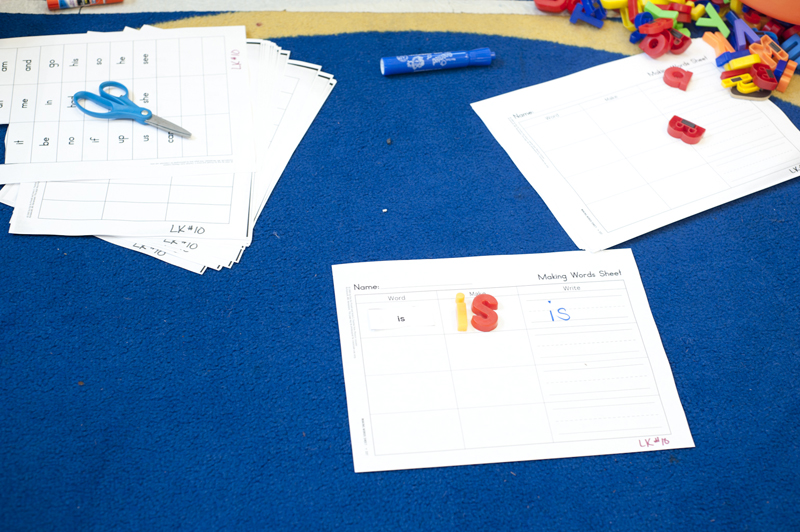

There are many situations during a typical day when a teacher needs to show students the correct way to do something (for example, the safe way to carry scissors). However, during Guided Discovery teachers turn to the students to model their own ideas. This sends the message that the teacher values the children’s ideas for using the material creatively and appropriately and trusts their ability to do so. As several children step forward to shape clay or draw a design with markers or look up a word in the dictionary, everyone in the class observes and learns.

“Now you will all be able to try some of the ideas we listed for using markers,” second grade teacher Ms. Martell says. She distributes sheets of cardboard and drawing paper. She then passes around the box of markers, asking each child to take two. At first, all the children work on the same tasks—drawing a figure, making a design, writing big letters—tasks that they just saw modeled. After a while, Ms. Martell says, “Now you can try out an idea of your own.” As the children explore, she walks around to observe their work, pausing occasionally to make a suggestion or redirect a student who has gotten off track.

After students have generated a list of ideas and a few children have modeled ideas, it’s time for children to independently explore the material. They tend to begin trying what was modeled. But with encouragement, they’ll soon start experimenting with new ideas. Although the teacher sets some limits on the task, the children still can make choices about how to do the task. They learn to turn to their own and their classmates’ resources rather than always looking to the teacher.

After a brief exploratory time, Ms. Martell, the second grade teacher, rings the chime to get children’s attention. “It’s time to share our work,” she says. “If you would like us to see your work, put it on the floor in front of you.” All but two children display their drawings. “Without talking, everyone look around and see all the good ideas!” There is a moment of silence as the children look. “Who would like to share one detail that you noticed?”

“Ramona used lots of different colors.”

“Ray’s design looks like lots of lightning bolts.”

The children continue sharing things they notice.

“Now who would like to tell us one thing they like about their own drawings?” Many hands go up.

There are many opportunities during Guided Discovery for children to learn from each other: they share and model their ideas, sometimes help each other during exploration, and at the end of the Guided Discovery they have an opportunity to share the work they’ve done.

Work-sharing is always voluntary; in order for children to feel free to experiment, they need to know they won’t have to make their results public. Ms. Martell lowered the risk of work-sharing by having the entire group display their designs at once. She knows that the more examples of each other’s work children see, the more opportunity they have to learn from each other.

The fourth graders in Mr. Alonzo’s classroom are finishing a Guided Discovery of rulers. “We’ll be keeping our rulers on the supply shelf with our other tools such as pencils, scissors, and staplers,” Mr. Alonzo says. “Who can show us a safe and careful way to put your ruler away when you’re done with it?”

Jocelyn volunteers. Holding her ruler by her side, she calmly walks to the supply shelf and neatly places the ruler in the box marked “rulers.”

“What do you notice about how Jocelyn put her ruler away?” Mr. Alonzo asks.

In the final step, the teacher engages the children in thinking through, modeling, and practicing how they will clean up materials, put them away, and access them independently at a later time. As in previous steps, it is the children who generate and model ideas.

Earlier in the year, Mr. Alonzo had already discussed with the children where and how the rulers are stored. He now trusts that Jocelyn can take the lead in reminding the class how to put the rulers away in their designated spot.

Guided Discovery has a deep impact on children’s learning. Children get interested in classroom materials and learn how to use them creatively in their academic work. They have opportunities to stretch their thinking and work independently. Perhaps most importantly, children are at the center of the process. Every aspect of Guided Discovery encourages children to offer ideas, act on them, and share the results of their work with others, which stimulates everyone’s thinking about future uses of the material.

Learn more about Guided Discovery with The Joyful Classroom and The First Six Weeks of School.

Paula Denton is the author of The Power of Our Words and coauthor, with Roxann Kriete, of The First Six Weeks of School.