We can’t help but make assumptions. We judge students continually based on what they say, how they behave, the way they respond when they are upset, and all sorts of other clues they give us each day in school. But sometimes the conclusions we draw are wrong.

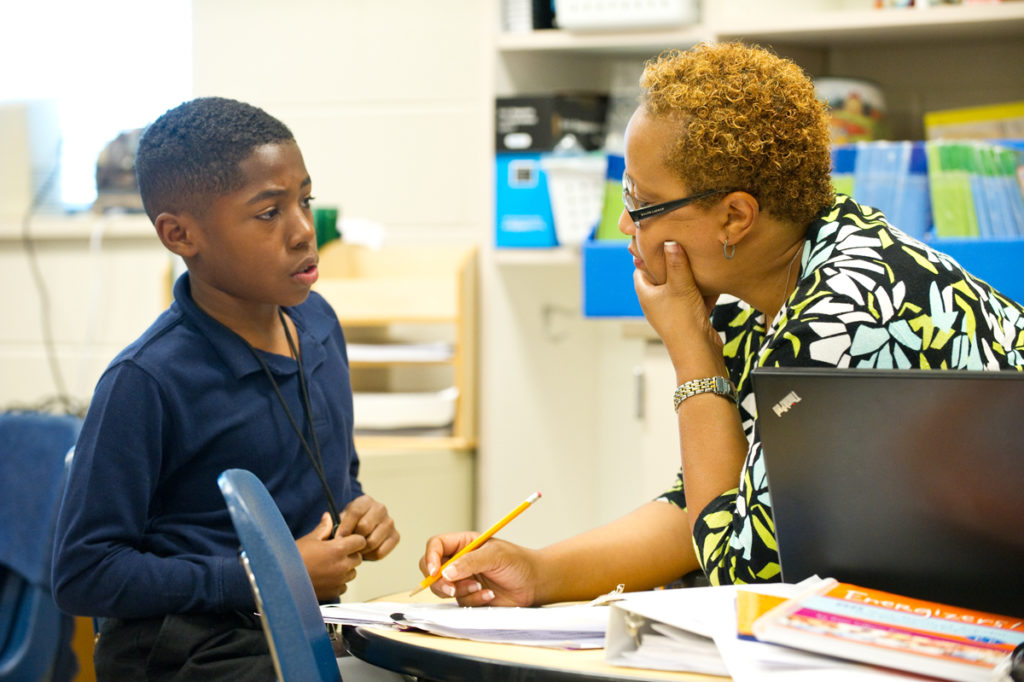

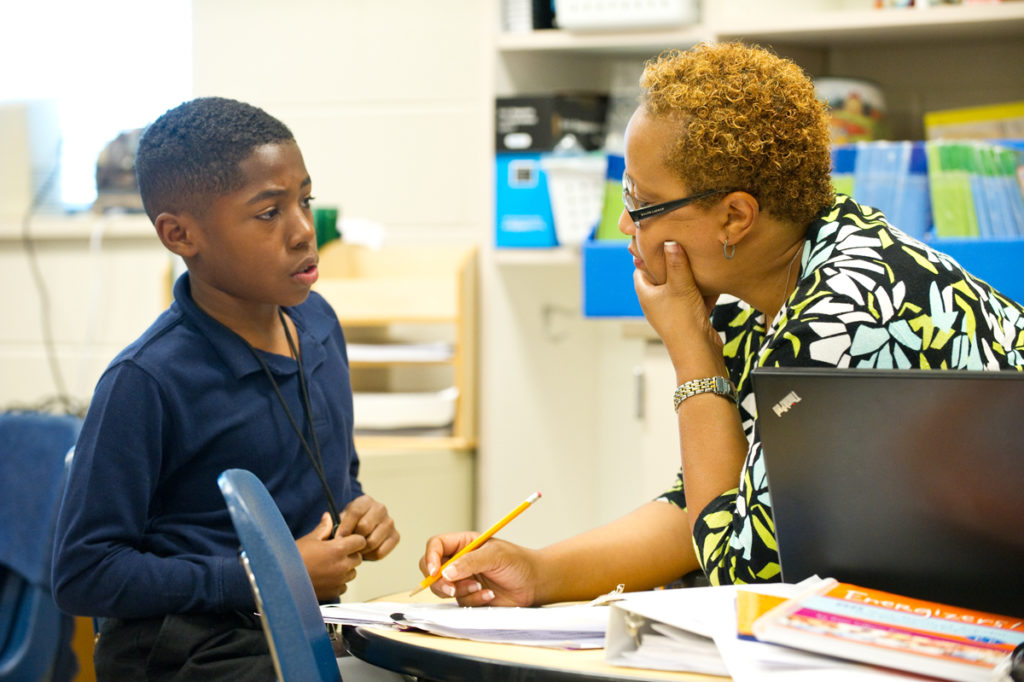

I learned this lesson during my second year of teaching, when a gift from a first grader spurred me to question my assumptions about him. In December of that year, this student was one I wasn’t sure I was reaching. He was often quiet, sometimes sad, and easily frustrated. His frustration was often directed at me, as I tried to help him move forward socially and academically. Because he was so often angry at me, I assumed that he didn’t like me or school, and that my efforts to help him had failed so far.

However, after dismissal for winter break, this student lingered behind in our classroom and shyly pulled a small pinewood derby car from his backpack. He told me he wanted me to have it because it was the most special thing he had, and therefore, the best gift he could give me. I realized this was the car he’d told us he’d spent hours making with his mom, the one that had won his Boy Scout troop’s pinewood derby race. Of course, I tried to give it back, but I quickly sensed that I was hurting his feelings by doing so. So I kept the gift, which sits in a place of honor on my bookshelf to this day.

I was surprised by this child’s gift and by the feelings that were clearly attached to it. I had wrongly assumed that frustration was all he felt towards me. However, the truth was that his feelings were much more complicated. Even though it was frustrating for him, he understood that when I pushed him to do more, encouraged him to stick with tasks that were difficult, or held him to a high standard, I did so for his benefit. I had misjudged him.

Children and their behaviors are often more complicated than what appears on the surface. One might assume that a child who is fidgety and seems distracted during whole-group instruction isn’t paying attention, but sometimes it turns out that she can repeat what was said almost verbatim. Or it might seem that a child who frequently questions or refuses to follow your directions dislikes school. But questioning authority may be his way of figuring out the world. A child with a strong sense of justice and fairness can exhibit what seems like defiant behavior.

So, as you enjoy some well-deserved rest during this winter break, take some time to think about your students. Are there some you don’t know as well as others? Are there some whose relationships with you or their classmates seem troubled? What assumptions have you made about them? As you rejoin your class in the New Year, try to look at your students with fresh eyes. I’d love to hear what you find out.

Margaret Berry Wilson is the author of several books, including: The Language of Learning, Doing Science in Morning Meeting (co-authored with Lara Webb), Interactive Modeling, and Teasing, Tattling, Defiance & More.